Side A

Hey, Ho, Nobody at Home

The Twig

Blue Ground

Offshoot

Side B

Swingin' Round

Quiet Mood

The Riddle

Yet We Shall Be Merry

Bill Smith, clarinet

Dave Brubeck, piano

Gene Wright, bass

Joe Morello, drums

What constitutes successful long form jazz? The answer might mean anything from a suite of tunes related by extra-musical titles, to a highly integrated work that stretches for an hour or more, with interdependent thematic, harmonic, and metric schemes. Over the course of jazz history, the elusive concept of a self-consistent long form has proven an irresistible challenge, enticing musicians as varied as Artie Shaw, Duke Ellington, Woody Herman, Eddie Sauter, Sonny Rollins, Dave Brubeck, Miles Davis, Wynton Marsalis, Chick Corea, Pat Metheny, and many others. The results have sometimes been hailed as masterpieces, other times derided as hubris.

Initially the Big Bands took the decisive lead in producing meaningful long form jazz. Jimmy Mundy's 1937 arrangement of "Sing Sing Sing" for the Benny Goodman Band still stands as a model of success. In it, whether deliberately or not, Mundy gave solutions for two great quandaries: how to integrate solos into the form in a meaningful sense beyond mere variations, while hinting as to the type of thematic material needed to sustain the form. Thematically, Mundy used two highly motivic tunes--interpolating "Christopher Columbus" into the original, to expand and sustain interest, while the solos functioned dynamically within the form.

The shift to more motivic melodic material was to become important, proving pivotal in allowing smaller groups to take the lead. Rather than sprawling melodies, demanding intricate pre-written arrangements to be expanded well, such as Ralph Burns's

Summer Sequence (recorded by Woody Herman)

, small groups could create loosely understood head arrangements, using highly flexible motives as the building blocks for longer, integrated "movements." The beginnings of this are seen in Sonny Rollins's

Freedom Suite. John Coltrane's

A Love Supreme, which can be heard as a fusion of Dave Brubeck's "Calcutta Blues" with the

Freedom Suite, showed further possibilities for this motivic style. Miles Davis's

In a Silent Way shifted the emphasis again, demonstrating how groove itself could play a larger formal role. Two decades later found Wynton Marsalis experimenting with the suite style of Duke Ellington, refining and expanding it until

In This House, On This Morning, which, while a septet piece, is symphonic in scope, with all thematic materials related to the opening. All of these ideas, modified through various developments in the jazz and classical avant garde, combined in Pat Metheny's

The Way Up.

The current of history isn't a straight line, however--no brief timeline or "history of heroes" can adequately outline the true means by which an art as complex and multifaceted as jazz is developed. Sometimes there are highly significant advances made which are overlooked for decades.

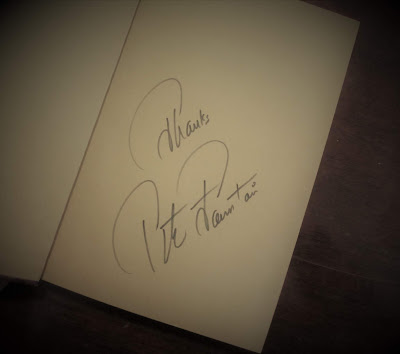

Bill Smith's The Riddle, the first of three studio albums devoted to his tunes, recorded in rapid succession with Dave Brubeck, represents just such a moment.

Bill Smith has lead a double life, musically, since the outset of his career. Straddling, with exceptional success, the worlds of classical and jazz music, he has substantially contributed to both artforms without gimmickry. His investigations of clarinet multiphonics in the 1950s, for example, have proven a permanent addition to our knowledge of the instrument, while his jazz has provided not just a path forward for clarinetists, but of formal compositional significance to all jazz musicians regardless of instrument.1960's

The Riddle is exceptional in this regard

.

Smith's goals with the album were clear from the outset:

My main interest in the album was to make 3/4s of an hour of well integrated jazz, unified by relating each tune to the English folk song, "Heigh, Ho, Anybody Home." [sic] In some of the tunes, the relationship is quite apparent as in "Hey, ho, Nobody at Home" or "Blue Ground, Swingin' 'Round" where it is used in the bass or where it is treated as a round. The relationship to the original in the others is more subtle (like a cousin whose only family resemblance is the eyes or a dimple or some other detail). "The Twig" is an out-growth of the last two measures of the original. "Offshoot" uses the tune in major considerably altered and expanded. "Quiet Mood" takes the second two-measure segment of the original and uses it as a point of departure. "The Riddle" [title tune] contains the original melodic shape but is played in shorted note values, while in "Yet We Shall Be Merry," the main tones of the original are lengthened and combined with a new thematic idea. [From the original album liner notes.]

The Riddle is poetically unique in both an aural and verbal sense. Aurally speaking, the original folk song "Hey Ho Nobody's Home" is usually sung as a round, with a melody bearing strong resemblance (call it a distant cousin) to the opening of "Sing Sing Sing". Whether Smith intended to highlight this connection to Benny (his boyhood hero), enjoyed it coincidentally, or couldn't have cared less is perhaps an added riddle. For me, this melodic similarity serves the overall aural poetic of jazz clarinet history, tying Smith to Goodman subtly.

The lyrics to the original folk song, only partially referenced through the title of the last track--"Yet We Shall Be Merry"-- are poetically linked to the project as well:

Hey, Ho, Nobody at home,

Meat nor drink nor money have I none,

Yet we shall be merry, very merry,

Hey, Ho, Nobody at home!

The lyric is a paradoxical knot, suggesting joy in either poverty or a bit of musical thievery, or both. This poetic is applied musically by Smith, taking this sparse communal round and making it the basis for a jazz album of original compositions.

Taken as a whole, Smith has given a blueprint for extended form jazz. The English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams (also known for pinching folk songs) quietly revolutionized the symphony in a similar manner. Taking his cue from modal English folk song and fantasia, he developed a symphonic style that eschewed the obvious development of sonata form, in favor of a new style wherein thematic cells were used in different ways, blossoming throughout works in expanding, original manner (the best example, perhaps, being his

Pastoral Symphony of 1922). By 1959, when the individual tunes for

The Riddle were being written, modal jazz was in vogue, yet successful long form usage of it was still to come. Just as Vaughan Williams's accomplishment has been often overlooked for it's subtlety, so has Smith's.

In the liner notes, Dave Brubeck added some thoughts:

The idea of unity in an LP should intrigue jazzmen, and Bill has given us one solution to the problem by relating all the themes. This is the first riddle of the album: to discover the thematic relationship of each of the tunes. The second riddle is to detect which parts of the music are written, and which are improvised. Almost everyone who has heard this album (including Joe [Morello] and Gene [Wright], our own rhythm section) has had difficulty separating the composed from the improvised sections. I take this as a real compliment, because good jazz composition sounds as though it were really improvised and good improvisation should sound as though it was as well thought out as a composition.

Since

The Riddle, thematic integration has become common and essential elements in long form jazz--Trane, Miles, Wynton, and Pat's albums all bear witness to this--but few have matched the unity, and continuously fresh feeling still evident in this album from 1960. There remains much to be said about Smith's unique and important mastery of the clarinet, along with his jazz application of that mastery. Those will certainly be discussed more fully in future reviews.

For the present, though it's ridiculous to rate anything this great, this album obviously gets

The Jazz Clarinet's top rating of

Five Good Reeds. The most frustrating riddle left is why this album hasn't been reissued, and why jazz history has neglected it for so long. Whatever the irrelevant answers to that quandary, those of us who have finally stumbled upon it will undoubtedly say "Yet We Shall Be Merry"!

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)